Landscape Ecology as a Hub

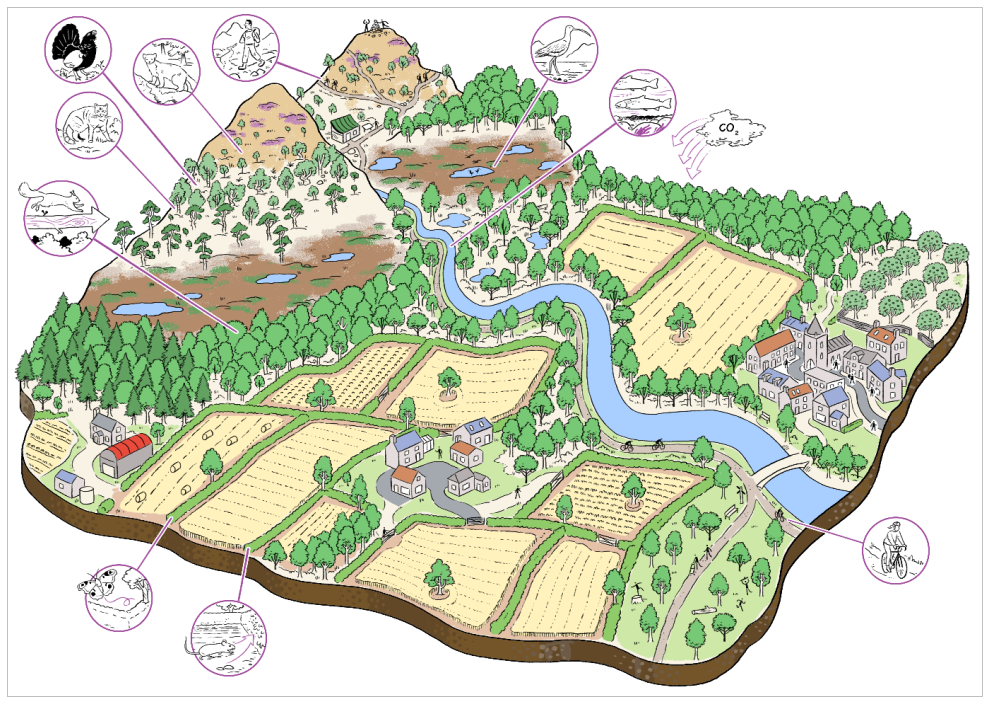

As a discipline, landscape ecology can be thought of as a hub connecting ecological, social, and economic elements, and it is this broad-ranging and interconnected nature which makes it hugely relevant to policy and practice.

Landscape Ecology is inherently transdisciplinary, relating to many different branches of knowledge and engaging multiple stakeholders to address societal challenges. At the heart of this is the understanding that ecological knowledge is incredibly important, but that it is ultimately a social and economic challenge to implement the huge changes required to tackle the biodiversity and climate emergencies we face.

Sustainability is a central aim for society in the 21st century, but it (and by extension, the idea of a ‘sustainable landscape’) is a contested concept in that its interpretation is dependent upon a plethora of different beliefs, values, and preferences. Because of this, dialogue is essential. Participation and knowledge exchange are key principles of landscape ecology, allowing researchers to understand the different perspectives of multiple stakeholders; enabling these stakeholders to influence research questions; and ensuring communication of research outputs in ways that are relevant and useful to policy & practice. Overall, participation enhances inclusivity & diversity, builds trust, and ensures that quality, innovative, and adaptive environmental management decisions are made.

The Policy Landscape

Even if you haven’t heard of landscape ecology before, you might have seen it being applied in policies at a number of scales and institutional levels.

With the 2020s being the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, there are numerous global landscape restoration policies and programs, and many theories and concepts of landscape ecology can be observed as being central to these. The Bonn Challenge, a global goal to bring 350 million hectares of degraded and deforested landscapes into restoration by 2030, focuses on restoring ecological functionality whilst also enhancing the wellbeing of people [highlighting landscape ecology concepts of connectivity & fragmentation & social & cultural landscapes]. The Endangered Landscapes and Seascapes Programme aims to be a ‘positive & creative conservation agenda’ which reverses biodiversity loss, enhances ecosystem services, celebrates art & culture, and supports local economies. Model Forests exemplify a landscape scale approach, providing a process for bringing a diverse partnership of stakeholders together to reach a common vision for sustainability across a large landscape.

Numerous national spatial planning policies in the UK are also based on principles which come from landscape ecology, with many stemming from the Lawton Principles which arose from the ‘Making Space for Nature Report' published by the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra) in 2010. This made the case for developing coherent and resilient ecological networks, and we have seen these implemented in a number of ways. Twelve Nature Improvement Areas were established in England between 2012 and 2015 to create joined up and resilient ecological networks at the landscape scale. Around the same time, ecological networks were embedded in Forest Habitat Networks and the Central Scotland Green Network in Scotland. Nature Networks have also been developed in Welsh policy. Landscape Character Assessment (LCA) is used in all four UK countries to identify and describe variation in the natural and cultural characteristics of different landscapes, and these feed into many types of environmental and planning decisions. The eNGO sector has also embraced the concept of landscape scale conservation, for example Futurescapes (RSPB), Living Landscapes (Wildlife Trusts), and Treescapes (Woodland Trust).

Landscape Ecology in Action

Whether they realise it or not, a huge range of professions make use of landscape ecology in their day-to-day work. This can be obvious - for example, landscape architects who may be involved in producing habitat creation designs, or ecologists exploring species movement across landscapes. But there are many uses that are less obvious. A farmer deciding how to manage their land across their whole holding is naturally thinking at the landscape scale. Farming and woodland advisers, and catchment coordinators, often have essential roles assisting land managers in making the best decisions for their business, as well as the local and wider environment.

Knowledge exchange is key in landscape ecology. Practitioners and policy makers can feed into research via interviews, questionnaires, workshops, participatory mapping, and co-design – or may use landscape ecology methods themselves (e.g. as part of citizen science programmes e.g. Natures Calendar). Practitioners can also make use of and benefit from research outputs through attending events or making use of evidence-based guidance (e.g. Applied Ecology Resources).

Have a look at our ‘a day in the life’ series to get a small taste of some of the careers that await in the landscape ecology world.

Text

Vanessa Burton and Landscape Ecology UK (2024) CC BY-NC

Image

Burton V., Metzger M.J., Brown, C., Moseley D. (2019) Green Gold to Wild Woodlands; understanding stakeholder visions for woodland expansion in Scotland Landscape Ecology 34 1693-1713. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-018-0674-4

References and Further Reading

Young, C., Bellamy, C., Burton, V., Metzger, M. J., Neumann, J., Griffiths, G., Porter, J., & Millington, J. D. A. (2019). UK landscape ecology : trends and perspectives from the first 25 years of ialeUK. Landscape Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-019-00945-1

Chazdon, R. L., Brancalion, P. H. S., Lamb, D., Laestadius, L., Calmon, M., & Kumar, C. (2017). A Policy-Driven Knowledge Agenda for Global Forest and Landscape Restoration. Conservation Letters. 10(1), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12220

Opdam, P., Luque, S., Nassauer, J. et al. (2018) How can landscape ecology contribute to sustainability science?. Landscape Ecology. 33, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-018-0610-7